For far too long, mainstream narratives have misrepresented Africa as a continent without writing systems or literary traditions prior to European colonization. This persistent myth that Africa was an “oral continent” devoid of scripts or recorded history has shaped global perceptions of African intellectual capacity and heritage. However, recent scholarship and growing awareness of ancient African writing systems are powerfully dismantling these misconceptions. Systems like Nsibidi, Meroitic, Ge’ez, and Adinkra stand as enduring proof that Africa not only had writing, but also developed complex, symbolic systems of communication rooted in philosophy, governance, spirituality, and culture.

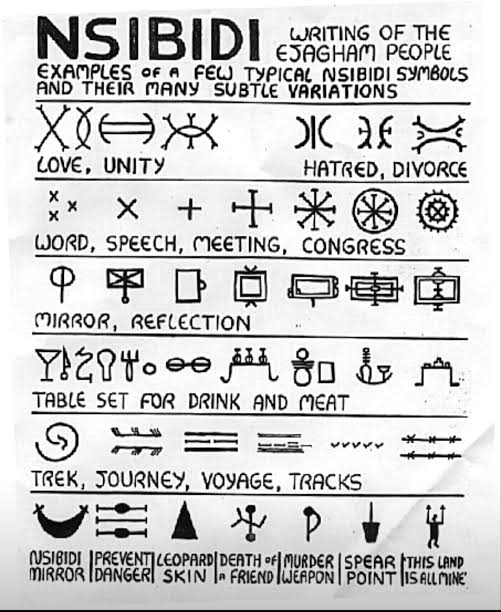

Nsibidi: The Visual Language of Southern Nigeria

Among the most intriguing African scripts is Nsibidi, a system of ideograms and pictograms used by the Ejagham people in southeastern Nigeria and southwestern Cameroon. Its exact origins are unclear, but archaeological evidence suggests Nsibidi dates back to at least the 5th century CE, possibly much earlier.

Unlike alphabetic writing, Nsibidi is made up of symbols representing ideas, actions, and relationships rather than spoken sounds. The system was used in communication, ritual, law, and art, especially by secret societies like the Ekpe and Ngbe, who used it to record laws, settle disputes, and conduct ceremonies. Nsibidi was inscribed on walls, calabashes, textiles, and skin, offering a rich, visual language that contradicts the idea of precolonial African illiteracy.

Meroitic Script: Nubia’s Forgotten Letters

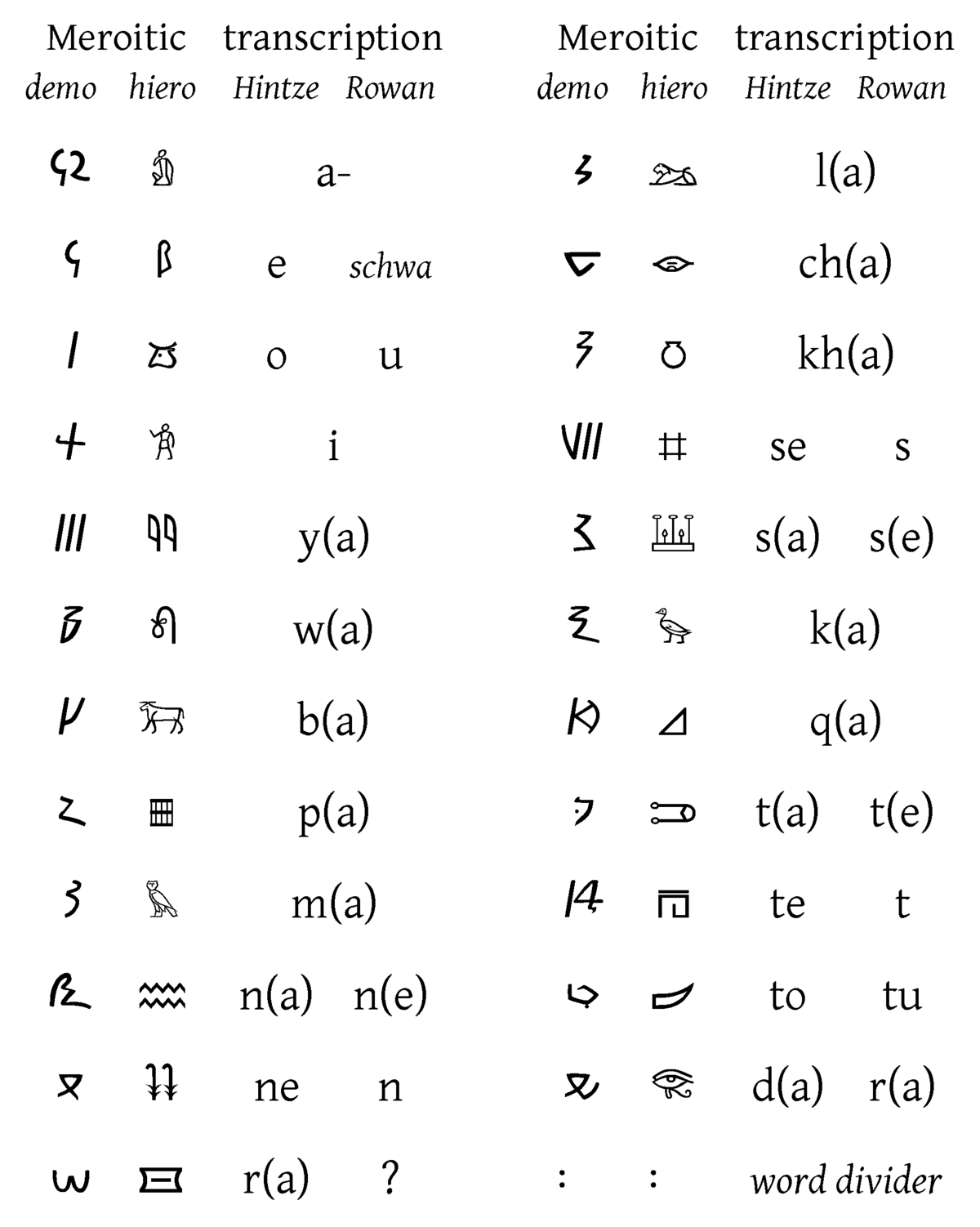

Another remarkable but lesser-known writing system is the Meroitic script, used in the Kingdom of Meroë, located in what is now Sudan. It appeared around 300 BCE and lasted for nearly a thousand years. The Meroitic language had two forms: a hieroglyphic script used for monumental inscriptions and a cursive script used for everyday writing.

Though still not fully deciphered, Meroitic is widely believed to have developed from Egyptian hieroglyphs but functioned as an independent writing system. It was used in temples, tombs, and royal decrees, indicating a high degree of bureaucratic literacy and administrative sophistication. Meroitic is a clear example of how African civilizations created their own literate cultures outside of foreign influence.

Ge’ez: The Script That Still Lives

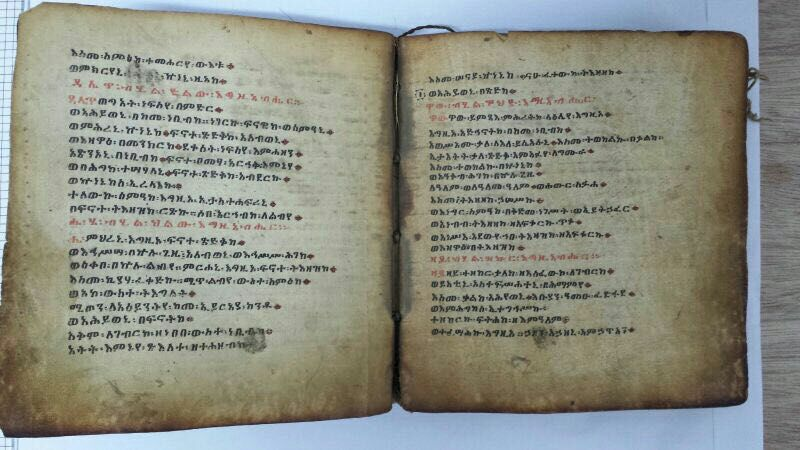

Ge’ez, one of the world’s oldest living scripts, originated in the Horn of Africa and has been used in Ethiopia and Eritrea for more than 2,500 years. Initially a purely consonantal script, Ge’ez evolved into an abugida (a script where consonant-vowel syllables are written as single units) and is still used today in religious, legal, and historical texts of the Ethiopian Orthodox Church.

In ancient times, Ge’ez was used by the powerful Kingdom of Aksum, one of the four great empires of the classical world. Stone inscriptions and manuscripts in Ge’ez show a literate elite recording theology, astronomy, governance, and philosophy. Its continuous use today makes Ge’ez a living link between ancient African scholarship and modern identity.

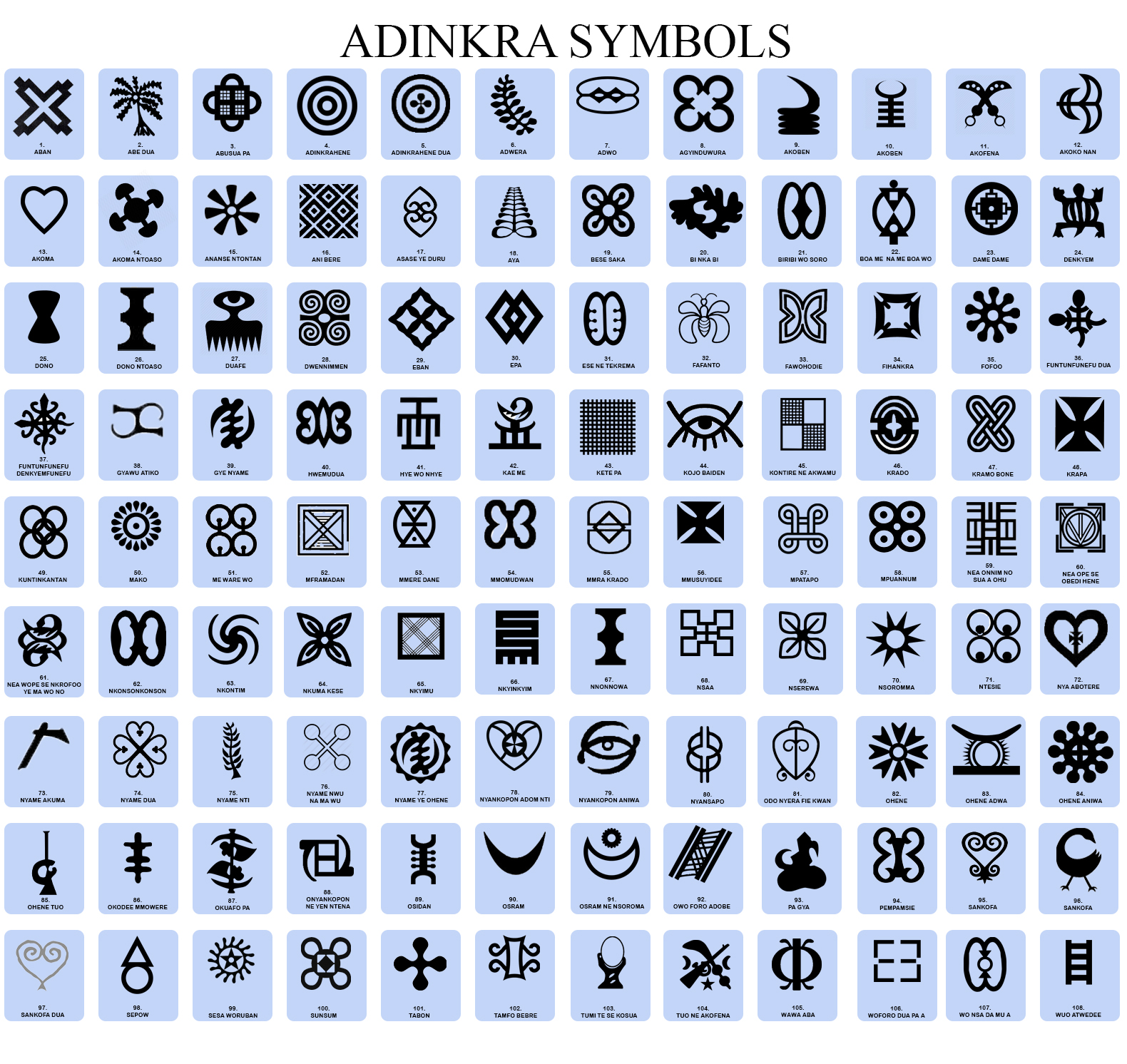

Adinkra Symbols: Visual Philosophy of the Akan

In West Africa, the Adinkra symbols of the Akan people of Ghana and Côte d’Ivoire form a symbolic language of deep cultural significance. While often used in textiles and pottery, Adinkra is far more than decoration, it is a visual system expressing moral values, philosophical concepts, and historical wisdom.

Each symbol represents a concept such as unity, bravery, patience, or divine power. For example, “Eban” symbolizes safety and security, while “Duafe” stands for cleanliness and feminine virtue. Though not an alphabet, Adinkra functions as a system of record-keeping and cultural transmission, challenging narrow definitions of writing and reinforcing Africa’s intellectual legacy.

Oral Tradition and Writing: Complementary Systems

Africa’s powerful oral traditions have often been misinterpreted as a lack of literacy. In truth, oral and written traditions coexisted and complemented each other across many African societies. Songs, proverbs, epics, and genealogies were performed and preserved through griots and community elders, while writing was often reserved for sacred, legal, and ceremonial purposes.

The misconception that Africa lacked writing stems in part from the colonial erasure of African knowledge systems. Colonizers often disregarded indigenous scripts, destroyed written records, or labeled African writing as “primitive” or “incomplete.” As a result, entire systems like Nsibidi and Meroitic were marginalized or forgotten for centuries.

Reclaiming Africa’s Literate Legacy

Today, scholars, educators, and cultural activists across Africa and the diaspora are working to recover and revive ancient African writing systems. Efforts include: research and partial decipherment of Meroitic by linguists and archaeologists; integration of Nsibidi and Adinkra into arts, curricula, and cultural programs; and digital archiving and study of Ge’ez manuscripts in Ethiopian monasteries.

These initiatives are part of a broader movement to decolonize African history, empower African scholarship, and give proper credit to the continent’s contributions to human knowledge.

Conclusion: Africa Wrote First

The discovery, preservation, and celebration of Africa’s ancient writing systems confound long-standing myths and rewrite the narrative about Africa’s intellectual history. From the coded ritual symbols of Nsibidi to the sacred texts of Ge’ez, Africa’s writing traditions show that the continent not only had writing but had it on its own terms, deeply woven into its culture, politics, and spiritual life.

These scripts stand as monuments to the complexity, beauty, and power of African civilizations, civilizations that were literate, philosophical, and deeply aware of their histories. It is time the world recognized that Africa has always had the pen and the power to write its own story.