Inspiration is similar to a wave that washes over the body. It is transient, crushing, the summum of revitalizing. It is bold, by virtue of its freshness, prophetic in its modernity, while also recentering.

It is a sensation that can last days, heavy yet immaterial, a glistening fog lingering demi-godly, murmuring in a grave tone, devoted like the shadows of your movements. As more days pass, you may feel the momentum dissipate, a spell wearing off like the chipping skin of garden cherubs, but what emerges and never leaves is a captivation for craftmanship.

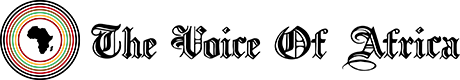

In early 2020, I visited the Robberg Nature Reserve in the Western Cape of South Africa during a trip that occurred right before the global pandemic revealed the enclosing cellophane attached to it. I didn’t know that the rippling waves I captured with my camera would later leave this indelible mark.

Walking down the trail and looking down, I saw the water crashing against the rocks, producing a subtle gradient on the blue scale, from a royal blue to the crystalline white that scintillated under the afternoon sun. The scene was not yet another plain, another unassuming sight.

The pattern of the sea conjured a feeling that was large and liberating. This feeling was, now that I think back, the likeness of a spiritual mirror, something like a corporal recognition of the undulating relationship between potential and actuality. And so, this is the opening window of this exposition.

These waves carried in my philosophy as a metaphor. Their stride represents the constant change ascending from our established neuroplasticity: an ability to alter our neurological setup acquired through the reimagining of the mind as a space, a model that comes along with the practice of intention as mining and the gift of repetition as cleansing. The image a wave presents to us is the embodiment of fluctuation, that is the substance from which consciousness covers new territory – the vital component from which our grey matter codes fertile alternatives.

In a more general sense, the wave is commonly used as a way to demonstrate the temporariness that is reflected by its brief gasp against the infinity of the upcoming waves. By design, the motif of these depositing waves finds its appeal by expressing such ephemeralness that our contemplative self is compelled to indulge in these hypnotic reiterations, in fascination for this ceaselessly recomposing natural form, an ode to life and divinity itself.

Oftentimes in storytelling, bringing time so viscerally into focus, the oceanic landscape is used as a tool to access a state of reminiscence. Through pathetic fallacy, it illuminates how, in the vastness of reality, a reality of such complete and overwhelming abundance, the self is so effortlessly susceptible to lose itself on its way. The waves express the introspective voyage a character may have upon his comings and goings, his experiences, and, in contrast to the waves eternal recurrence, his finitude.

In The Heart of Understanding, Thich Nhat Hanh takes this existential view a step further with one advice: “If a wave only sees its form, with its beginning and end, it will be afraid of birth and death. But if the wave sees that it is water, identifies itself with the water, then it will be emancipated from birth and death.” There, he explains that to mainly see our temporary condition through the time limit set on our human biological clock induces fear, fear which stifles understanding.

In contrast, to tend to the spirit, to concentrate on the expansive nature of our mental experience rather than the inevitable wilting of our physicality repositions our passage on earth as the natural circulation of energy it has always been. This frame of mind is what gets us further from the whims of the material world, closer to our essence, our presence, from that which follows our most fruitful creations. To hold this perspective over the experiences we encounter supplies greater freedom, more generous interpretations, and material to mold structures interpretative of this more liberated spirit.

This metaphysical approach taken on the individual can be stretched and transferred over to the collective. Collective consciousness could gain more clarity, more fluidity from understanding that the historical functions much in a similar way to the tide. The ebb and flow motions are directly shown by cultural movements in their spontaneous and reactionary drifts. It is not a process of birth and death, but rather a dance whose movements, while uncoordinated, still remain in conversation. Things fall apart and are rebuilt, but nothing ever really disappears. Like portals, ideological movements add layers to our reality, and as if imprinted in our collective memory, contribute to its development over time.

Human history can be defined as the ambiguous juxtaposition of sequential cultural movements. When mentioning the Abolitionist Movement, the Harlem Renaissance, or the Civil Rights Movement as seen in American history, how can one clearly confine any of these wide-reaching stems other than in some arbitrary timeline? The roots which constituted their growth are all entangled in each other in an eclectic chronology. And what more, each of these movements are infused in the present we inhabit today. The act of introspection reveals that, whether intentional or not, divergent social constructions work in superposition. These movements were already existing, in smaller threads, within the progressive advancements of human thinking. Neologisms reflect these cognitive milestones. Any movement is found in pieces, scattered in the multiplicity of the movements that have preceded. The introduction of any readily recognizable historical turn is only manifest of a long-winded minutia of ideological sand deposited to dune, eventually tipping the scale.

Counter-culture movements emerge when the direction of these turns bring about a range of negative consequences for a distinctive group of people, which out of mutual interest, decide to collectively push back against the oppressive flow of the movement. This subversive side of the collective join forces to rise against the upcoming wave, in an attempt to sway popular opinion in the opposite direction of the current. The Anti-Apartheid Movement in South Africa is a prime political example, but this phenomenon can also be observed throughout the course of mainstream artistic movements. In European art history, Realism, a movement that favored a certain cynicism and objective presentation of the world, is largely understood as a response to Romanticism. Some might say it arose in direct opposition, seeking to pervade the vision the Romantics crafted of an idealist and emotionally heightened reality. The turbulences that occur between these groups of people arise from their intrinsically different visions of the world. As a result, views clash, before, in some unexpected way, they eventually converge.

Understanding currents, how they take form, and how they flow is a natural next step. Is to master social dynamics to study the basic mechanisms of energy? It seems so.

Therefore, I will begin to observe them under the optic of water – the natural element these social dynamics most visibly seem to emulate. And to understand how a flow state can be crafted, maintained, and tuned to a channel of constructive energy circulation, the laws of thermodynamics are instinctively called into question. The exploration of these properties starts to excavate the underlying forces that are at play when groups of people come together with a plan. In fact, by practicing this notion of essence rather than form, I believe it is possible to participate in the design of an African utopia.

The first law of thermodynamics states that “energy cannot be created nor destroyed”. If water is akin to energy, its circulation can take many shapes while still remaining itself. This applies to forms of government. The outlook on Africa that has been fit for beneficiaries, has been usually that of an ill-fated, sunken place, whose past and current exploitation has rendered the systems in place broken, beyond repair. Although one cannot forget the conditioning of suffering that afflicted the continent in irrevocable ways, this outlook is purposeful in smothering hope, asphyxiating will, and killing action. In truth, to conceal the tracks laid by the prosperous African civilizations, such as The Wagadu empire, The Mali empire, or even the Songhai empire, is to hide a great source of energy: energy the first law applies to. This is no attempt to conjure some stale sentimentality or misplaced nostalgia, but rather to inform that, like suffering, these parts of the heritage also undeniably form the backbone of the African people in this day and age. It is inherited knowledge that can allow us to be discerning of what there is to salvage, and to let go, in order to build our future.

The archival work done by African historians is invaluable in terms of the preservation of cultural identities in their most authentic light. Thinkers from The Négritude Movement, the Pan-Africanist Movement, and the budding Afrofuturist Movement have purposed to reinvigorate African consciousness with the sense of pride that was historically trampled on, by those who through exploitation, sought financial gain. This unionizing work came along with a memorandum to accentuate and accelerate the recovery process of our past. To start with what we have: the Earth’s oldest record of humanity. This inclination towards anthropology aspired to reconcile the remnants of lineage with a fragmented cultural identity that, additionally, was subject to a false notion of cultural inferiority. It laid a foundation upon which to reject fabricated narratives and counteract the practical forgetfulness of the African man’s birthright to the ownership of African land. Then came the proposed way of identifying with a collective direction of thought; a task requiring the most beneficial findings of social epistemology, and to be preferably undertaken with the acceptance that institutions are intrinsically dynamic instead of static, so that a fundamental margin of adaptability can trickle into the commencement of any sustainable social reorganization.

The second law of thermodynamics states that “for a spontaneous process, the entropy of the universe increases.” If water is akin to energy, any shape it lands on will contain an increasing degree of instability. The task of drafting a governmental system that isn’t set to fail in some way or another is, by most standards, considered illusionary. From the ancient Greek philosophical tradition, Plato’s Republic emerged as one of the first and most influential treatise on the formation of a utopian state. Even its brilliant craftmanship, its painstakingly thorough attempt at accommodating a place for justice to reign over all aspects of society cannot save it from the fragilities that made this project so far unrealized. But in effect, it is inspired by this blueprint that I can now postulate that the measure of a system’s success is set by the measure of this system’s failures. It is clear how, the more functional a system, the narrower its margin of error. The term ‘failed states’, is a controversial descriptor used for countries notably in Sub-Saharan Africa, that exemplify how tragically order tends to disseminate into chaos. Besides reasonably, some degree of chaos always preexists. But somehow, it seems that even the most well-engineered designs should include spaces for imperfection. It is how exactly to predict this margin that is worthy of analysis.

The human experience is the experience of being in transit. The existential angst that we may feel derives from the perpetuity of continual waves of change. This sensitivity is usually less developed in youth, when the view of the world is more limited, and by intended circumstances, a novice’s adequately sized mental configuration. Growth ensues through an evolution of juxtaposed microstates. With time, the world expands, complexifying with the maxim that it was never square cut but rather a conjunction of the many achievements and failures of those who came in passage. In Philosophy for Passengers, Michael Marder describes how the human experience holds great similarities to passengerhood. The idea of travel is weaved into the conception of our own personal storylines. The character’s journey archetypically goes from one point to another, whether that is presented externally or internally, or whether both points end up being the same. This personal journey involves a certain degree of chaos before reaching some upper ceiling. There’s a directly proportional relationship between experimentation and discovery, or one could say, the expansion of our self-cartography. And so, any truly human structure must have a margin of error, one I would equate to a margin of freedom. Systems can reach a new level of self-awareness by seeking to shed light on their blind spots.

The third law of thermodynamics states that “the entropy of a perfect crystal is zero at absolute zero (Kelvin).” If water is akin to energy, the most perfect shape it can take requires that all energy be used up. The term ‘utopia’ was coined by Thomas More in his 1516 book Utopia, which begins when More takes a trip to Flanders, Belgium, where he meets the character Raphael Hythloday, a world traveler that narrates his experience in Utopia, an island he gives testimony as the best running form of government he’s ever witnessed. Utopia translates to “no place”, a meaning that corresponds with the idea that this societal ideal is impossible to achieve, the equivalent of absolute zero. The temperature of absolute zero can only theoretically occur when each ion exhibits no motion, while fixed in a perfectly ordered crystalline lattice. The scientific explanation for why it’s inconceivable is that it would require an infinite number of steps to reach. So realistically, entropy will always persist in the form of minimal heat energy. Similarly, a utopian ideal would require an exhaustive level of energy exerted to impose the kind of order that would translate to a perfectly harmonious cohesivity. The societal explanation for why it’s inconceivable is that to mold this theoretically perfect structure would require infinitely specified regulations permeating at all levels of the design. So realistically, this impossibility will always manifest itself through small degrees of disorder.

And yet, there can be no severance with the need to be working towards an ideal. Even with its inherent contradictions, the ideal is what keeps the spirit going. Utopia is a place that we cannot reach and a place we cannot but reach for. This is when we arrive at the question of what exactly we are aiming for. Is there even such a picture in mind? What is the place we are so euphoniously drawn to? What is the utopia we’re trying to construct for ourselves? And considering all these different versions of utopia, how can there be space for all of them? How can all individual utopias fit within a universal utopia? Is there a form of society that supports our individual and collective contradictions? One thing is sure: the design of this society is not for one person to draw. It must unescapably be a collage: an exquisite corpse from which a sanctified body of work would surface. The destination is still mystifying and abstract. But in musing, this new movement would employ a compromised merging of idealism and pragmatism: a neo-utopianism that could prevent the harmful uses utopian ideologies have taken throughout history. In order to be accomplished, this movement would need both rigor and experimentation. The idea of balance, in such a case, becomes an important research subject. Indeed, a paradox lies in the fact that an excess of experimentation paves us a road straight down to chaos, while an excess of rigor creates something sterile, something devoid of the humanity that makes us.

The underdevelopment of Africa gives it a vantage point that other parts of the world cannot benefit from. It is the opportunity of having a baseline from which to innovate in the domain of societal conceptions, whether that concretely articulates in terms of urban planning, ecological and educational institutions, or government structures whose current forms under late-stage capitalism already show their true effectiveness. As its own independent entity, the third world doesn’t have to follow the preconceived mold other societies have left but can instead shape its own. Africa holds the ability to forge paths that haven’t been taken and find new avenues of possibilities for itself and future civilizations across humanity, not only intercontinentally. In The Journey of Humanity: The Origins of Wealth and Inequality by Oded Galor, he explains how “the proliferation of distinct cultural norms contributed to the variation in the movement of the great cogs of history across the globe”. Subsequently, the prospect of African development gives floor to the historical deviation that can give rise to a brand-new strand of divergent social constructions. No doubt will they bear their own revelations and challenges. But that’s why a global perspective is useful in remembering the mistakes of past, recorded, and available in a plethora of case studies. The movements to come in waves out of Africa have the potential to be revolutionary once the purest forms of radical intention have infiltrated the most inner corners of its consciousness.

Water as an element is indispensable to our health, a universal solvent that, from its biological relevance, we can all recognize as a reference. It aliments the body’s activities of self-preservation that allow us to perform the daily tasks that we are meant to do to survive. Water as a metaphor guides us through the mundane, awakening of the self to the fluid membrane of reality. It prompts the mind to wake up to a reality that gives permission to dream of itself and its reformulation. Ytasha Womack says, “The imagination is important. The imagination is a lifeline. The imagination is an extension of the resilience of the human spirit.” We nourish ourselves from that source and are meant to be pouring back into it. With the number of resources we possess, the collective should be inclined to participate in the recycling of clarity. It is shapeshifting, muddied and sometimes very faint but it’s free flowing. In a river of possibility, there is an isle where African utopia has actualized. To take flight, our past, present, and future must delineate from this principle of fluidity.

This is so beautiful!

Wow Lenie, I love this piece. You never stand in the same river twice, so who knows what is coming downstream 🙂

[…] Read Also: On African Utopia Part 1: Water As a Metaphor […]