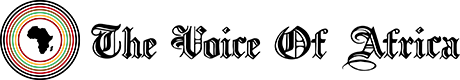

Skin, an hour-long documentary film available on Netflix, features various Nigerian women’s experiences with skin tone discrimination, most commonly termed ‘colorism.’ Colorism as a term is described by the American feminist writer Alice Walker as the “within-group and between-group prejudice in favor of lighter skin color. It is a “global cultural practice” that manifests “among people of the same ethnic or racial group” (Night, 2015; Salaudeen, 2020). For most of the world, having darker skin is perceived as a bad thing and it is even worse for women of deeper complexion. Yet, over ⅔ of the world is composed of people with deeper complexions, even in northern regions (i.e. indigenous peoples in North America). This documentary beautifully explores the rather contradictory phenomenon of colorism in the context of Nigeria, one of the world’s largest consumer of skin lightening products.

“Oh, you’re so black!”

Nigerian makeup artist Teniola Kashaam often heard this from a lot of people including aunties.

Throughout the documentary, the viewer is confronted with the raw emotional and structural violence of colorism. Even though the film devotes a lot of time to exploring bleaching or skin lightening use by women of the society, multiple points were made about other areas, such as the film industry, the economy, and spirituality. Things like the attribution of lightness to the quality of a person or the success-ability of an individual were not neglected in the documentary. “Growing up I wanted to be every shade other than the shade that I am,” says life coach Eryca Freemantle because, as British-Nigerian actress Diana Yekini put it, “dark skin wasn’t in… it wasn’t fashionable, it wasn’t sexy, it was cute, it just wasn’t.”

The documentary pulls at this notion of the disdain of ‘blackness’ by employing a side by side, kind of back and forth, testimonial style between Diana Yekini, who is of a dark complexion and has short tightly curled natural hair (4c) and Eku Edewor, a mixed actress with a very light complexion and longer looser curl natural hair (3b). While Yekini spoke of hearing things like “if only you had lighter skin” ore being attacked in the Nigerian film industry because of her skin complexion, which eventually resulted in her resigning from acting, Edewor spoke of “knowing that the role was hers” and always having opportunities in the industry. Though Edewor did mention that she had to assert herself because of doubts about her authenticity due to her mixed-race, there was no doubt that as a person of lighter complexion, she got more positive attention—- her skin color automatically co-opted her into a realm of privilege.

In the documentary, popular Nigerian rapper Phyno also shared an experience he had with colorism in the Nigerian music industry. As Phyno was preparing to shoot a music video, the director explained to him that it often was easier to work women with lighter skin tones due to lighting effects. Basically, with people of lighter complexion, the lighting does not have to be modified too much which makes for an easier work environment. According to conceptual artist and photographer Mudi Yahaya, this issue of lighting can be explained by understanding the process and history of film and picture development—which determines how light and color show up in the film or picture. In the past, the medium through which images and motion pictures were stored was film stock. As Yahaya explains, “different film stock reacts [differently] to different types of skin tones.” And since the most popular film stock was Kodak’s ‘Shirley card,’ in which the tones were reflected that of a white person’s skin, there was a bias in the film to black skin. As technology has advanced we no longer use film stock to record images and videos, but film stock did serve as a foundation to how we understand film and photography. Therefore, there remain biases, as Phyno’s experience illustrates, in being able to adequately capture darker skin, conveying notions of colorism in the film and photography industries.

To further complicate the societal normalization of colorism, there is an economic favoring of colorism due to the notion that lighter skin requires more maintenance. The products used to attain lighter skin are fairly expensive for the poor and working-class, thus a lighter skinned person is viewed as high-maintenance and higher class because they are able to afford skin lightening products. In the documentary, this phenomenon is framed as ‘the politics of skin.’ Nigerian social media influencer Idris Okuneye, popularly known as Bobrisky, explained that growing up they were determined to get out of poverty; the question was “what would get people’s attention?” Bobrisky soon took to bleaching products to increase their desirability in society and to sell the very products that they hoped would take them out of poverty. And it worked! According to Bobrisky, they are now able to sell about $1,500 worth of products a day, and with the added perks of being a well-known social media influencer, they are far from impoverished. The fact that lighter is profitable is also illustrated in the documentary by cosmetics brand owner Leslie Okoye. Leslie explains that as she was launching her business, she knew that even though none of her products contained bleaching ingredients, if she did not put the word ‘lightening’ in the name, they would not sell.

Products like black soap (alata samina), commonly used in African households, use models of lighter complexion, rarely those of deeper skin tones, and promise fairer, lighter, or in a more coded sense, ‘toned’ skin. The documentary featured a cosmetics seller who had rebranded her bleaching products as ‘toning creams,’ but they served the same purpose as before: they lightened the skin. Or, a point that I was surprised about, the rebranding of bleaching products as toning creams makes it seem like your natural skin color features lighter tones that can be ‘naturally’ brought out by the products, thus making it seem like the deeper shades obscure the true lightness within you. How psychologically harmful is that! It is easy then to see how people can come to hate their darker skin because it is seen as an obstacle that prevents them from being their true ‘beautiful’ selves.

1 Corinthians 15:40-41 (Good News Translation)

“And there are heavenly bodies and earthly bodies; the beauty that belongs to heavenly bodies is different from the beauty that belongs to earthly bodies. The sun has its own beauty, the moon another beauty, and the stars a different beauty; and even among stars there are different kinds of beauty.”

The documentary also made a point about the spiritual dichotomy of whiteness and blackness, as whiteness connotes good while blackness connotes evil. The Nigerian actress Hilda Dokubo speaks of this in the context of Nigerian traditional religion. She speaks of the Yoruba water spirit taking on two forms, an evil one whose masquerade color is black and a good one whose masquerade color is white. I found this perspective interesting because issues of skin tone privilege or discrimination are easily attributed to the things of the white man. Yet, in this example presented by Ms. Dokubo, African traditional religion also plays into these color sentiments. This had me wondering whether there are ways in which we emphasize the West or the western gaze in relation to things of our culture, religion, society etc., when we need not to.

This example of the spiritual dichotomy that the documentary brings up has led me to consider how far we can employ the black-white paradigm within colorism. Let’s consider the possibility of translation issues: the white/black assignment in these spiritual interpretations and representations may be based on the sentiments these colors hold within the English language rather than in the Yoruba language. For example, does the Yoruba description of the water spirit in her two forms carry the same sentiments of black-white, good vs. evil, or might it be more of a consideration of light and dark. In bringing up the dichotomy of spirituality, Ms. Dokubo seems to suggest people considered to be black are perceived as evil or bad, because in the English language blackness is associated with bad. However, Africans do not generally characterize themselves as black. So, it would be difficult to say that we implicitly characterize ourselves as ‘bad’ because of this black/white distinction, certainly not during pre-colonial times. In short, ‘black’ may not be the right word to use when considering if pre-colonial, indigenous beliefs carry colorist notions. Thus, Ms. Dokubo’s argument still holds using dark/light as the factors of distinction rather than white-black, since colorism plays into the idea that if you are closer to white you are more favored

From the young child who spoke about how she doesn’t ‘want’ to be “black-black” (as if she had a choice) to the burned bleach seller who tearfully regretted that she could not return to her natural color, the documentary “Skin” makes us realize without a doubt that colorism is a problem. Furthermore, it’s effects are seen well beyond Nigeria, and as a Ghanaian watching this documentary, I could see many parallels between how colorism is perceived in Nigeria and Ghana.

“When I get married I won’t be as fair as this… I’ll be comfortable then.”

-Skin lightening cosmetics seller in the documentary

Recently, I’ve been reading Jemima Pierre’s Predicament of Blackness: Postcolonial Ghana and the Politics of Race, and something I have come to understand is that the dynamics the documentary paints about Nigeria is the same in Ghana, “from media affirmation of light skin as beautiful to everyday practices of light skin valorization” (p. 117). I cannot count how many times I’ve heard Ghanaians talk about someone’s color, and more often than not the color that is liked or the nice color is the lighter one. There is also an obsession in the Ghanaian for people with a naturally lighter complexion to maintain their skin color. For example, In Ghana, as a brown-skinned girl, I would be labeled as fair but in the summer I tan–a very natural phenomenon–and so my summer shade is almost two to three shades darker than my winter shade. By the time I was ten years old, people in my Ghanaian community noticed how melanated I am in the summer compared to the winter and began to advise me on how to “maintain my color.” Constantly, aunties would ask me if I’ve tried this or that: “oh try cream wei,” “oh use saa samina ɛbɛ boa paa!” So I began using certain lotions and sunscreens, not for the common benefits of moisturized and protected skin, but because I wanted to “keep my color.” Growing up like that was frustrating because I loved my skin, darker or lighter, but I hated the possibility of some Ghanaian auntie making an offhand comment.

In 2005, Agyeman Badu Akosa, the director-general of the Ghana Health Service launched a campaign against bleaching products. He reasoned that the issue of skin lightening in Ghana is transgenerational and cuts across class and gender, thus making it a very serious matter. Even in the Ashanti region of Ghana, “if you are nominated and installed as a queen mother you must lighten your skin before the enstoolment,” because “it brightens you up… in much the same way as putting light in the room.” Again, we see this phenomenon of villainizing darkness and glorifying light, in relation to people’s skin tones. In 2017, the Food and Drugs Authority of Ghana banned the importation of all products that contain the skin-lightening chemical, hydroquinone. This is a great administrative move towards discouraging colorism in Ghana, but whether bleaching is there or not, colorism persists in society. Whether it is comments like ‘I like your color,’ or people of lighter complexion receiving “better opportunities and treatment in society” than people of darker complexion, colorism remains a large concern in Ghana—- and many other societies in the world.

“Many blacks, in short, simply want to be beautiful and successful. But because no black can be white, it follows that there must be some other, achievable point of being beautiful and successful that is aimed at in such activity.”

–Lewis Gordon, Her Majesty’s Other Children.

[…] out as gradually African deaths joined the global toll. Now, we see that in our own backyard that Black people are among the highest affected populations of COVID-19. Existing data show that the mortality rate […]